Jennifer Wilson: An Interesting Egg-sperience

This story contains descriptions and images of blood and animal experimentation.

* * *

After four hours in a wobbly lab chair that gives most students back problems, I was worn out. Surrounded by a bloody mess of cracked eggs shells, chicken heads, and feathers, I was ready to never look at another egg ever again.

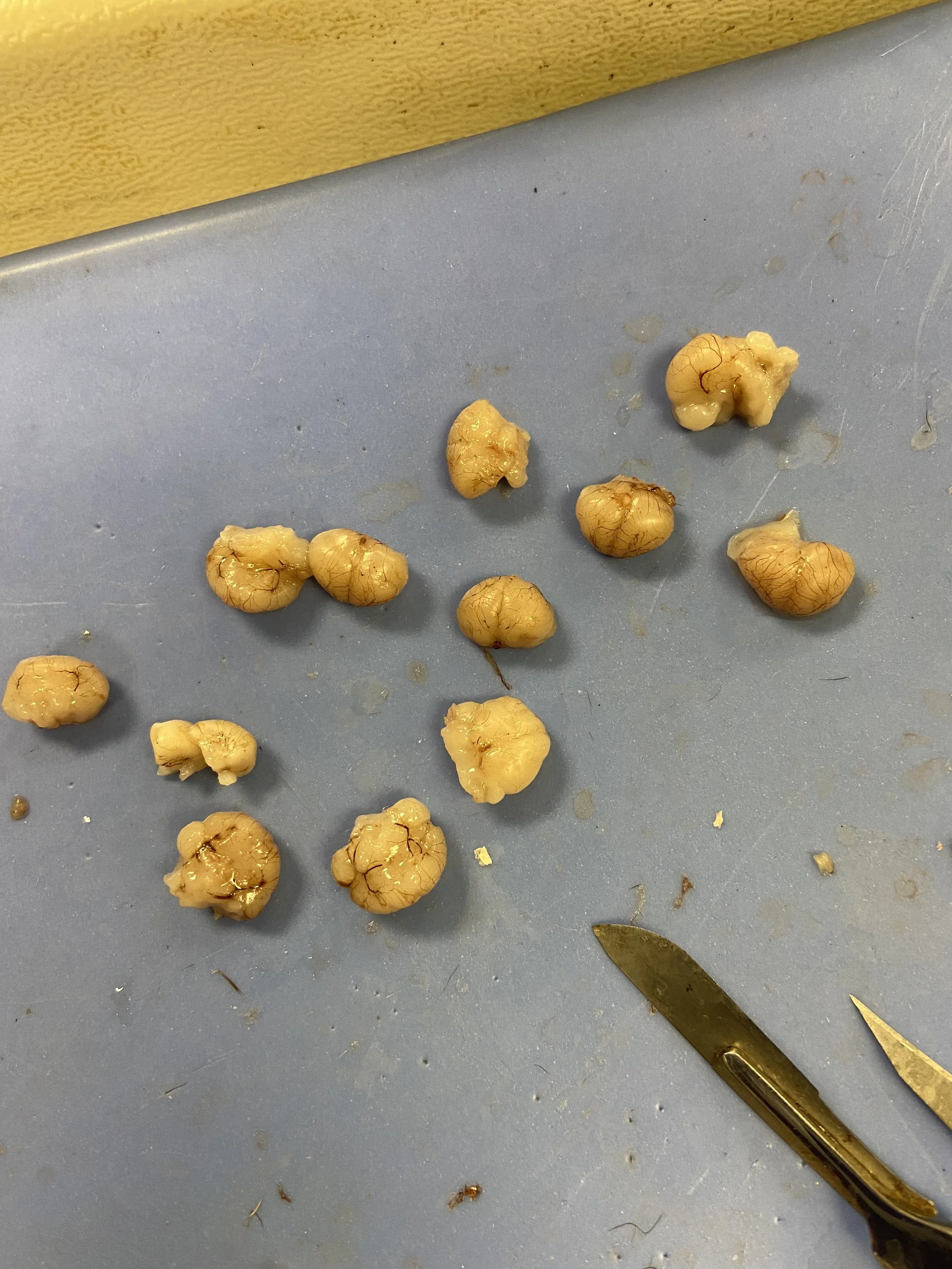

Then I looked over, away from the mess, at my neat pile of freshly dissected chicken brains, and I thought to myself, “holy crap, this is so cool. I just got to handle chicken brains all day.”

Chicken brains that Jennifer dissected

This semester, I conducted independent research at Lander University where I studied the effects of nicotine on the grey matter thickness in embryonic chicken brains. Some of the work that I completed for this research included injecting fertilized chicken eggs with nicotine solutions, dissecting the developed chicks to obtain their brains, and processing and slicing the brain tissue. A typical day for me would be spending three or four hours in the lab, sitting in one place watching a microtome thinly slice a chick brain, only to end up getting one successful tissue slide that was good enough to view under the microscope.

One of the first steps of my experiment was to inject nicotine into the chicken eggs. The day that I did these injections was very important, both for me and for my eggs. My research professor explained to me that I was to use a Dremel (a type of power tool) to make a tiny, tiny hole into the blunt end of the egg, and then I would use a syringe and needle to inject the lethal nicotine solution into the hole. Easy, right?

But this fear kept gnawing in the back of my mind: I had to do all of this work alone. There was no other research student that I could make do the hard parts of the experiment. No one that I could double-check with at the last second before I made a permanent move, like drilling a hole into an eggshell. It was all up to me, and that was terrifying.

What if I drilled too hard into the egg and it burst open? What if I accidently inject too much of the solution into the egg and it killed the embryo? What if I accidently stabbed myself with the needle and could die of nicotine exposure? (This was dramatic, but it was still a thought). Or worse, what if I contaminated the eggs and they all died, and then my experiment was ruined?

With all of these thoughts crammed into my mind, I walked into the lab with weary confidence. The lights flickered on, and I could hear the faint hum of the incubator holding my forty-eight fertilized chicken eggs. I set my bookbag down, took a deep breath, and stared at the empty lab table in front of me.

I knew I needed to work quickly because the more exposure the eggs had to the air, the greater the threat of contamination. To work quickly, I needed to be as calm as possible, and for that to happen, I needed to be as best prepared as I could for every part of the injections. I went over the steps in my head about three times before actually beginning the set-up, and then I finally started to gather my materials.

I grabbed a bottle of ethanol that I would use to sterilize the eggs and laid out paper towels so that they would catch any dripping chemicals. I checked to make sure I had both tubes of my nicotine solutions, and I put them on opposite ends of the tube rack so that I wouldn’t get them mixed up. I picked up the Dremel and made sure it was charged and working, and I grabbed two syringes and two needles that I would use for the injections. Lastly, I picked up a purple roll of lab tape, tore off 16 pieces, and stuck them on the edge of the table for easy access when I needed to cover the hole on the egg.

I stepped back from my lab set-up and was content with how it looked, but the fears and “what-ifs” started creeping up on me again. I brushed them away, however, because I knew this had to be done. It’s now or never.

Jennifer’s lab table during her dissections

I unlocked the door of the incubator to grab my eggs. The warm, humid air puffed in my face as I carefully took out my first tray of 16 eggs and placed them on my lab table. I wiped the eggs down with ethanol, picked up the Dremel, and was ready to go. There was one problem: my hands were shaking like crazy.

I took a breath and told myself to chill out, it’s not that big of a deal. I started drilling the first egg, but because my hands were shaking, the egg started wobbling around in its little crate. The fears in my head seemed to be growing louder, and I felt like panicking. Even so, I knew I had to get a grip and keep going because of the risk of contamination.

Finally, the egg stopped wobbling and a small hole appeared where the tip of the Dremel pointed. I knew I had completed my first drill successfully with no crack in sight. I reached for the syringe, pulled up my first nicotine solution, and crouched down at eye level so that I could see exactly how much nicotine I was inserting into this egg. Once injected, I covered the hole with tape, and went onto the next one. I breathed a sigh of relief and could already feel my nerves start to calm down.

After the first few eggs were drilled and injected, my fears were almost completely gone. My heart rate slowed back down, my shaking went away, and I was in the zone. Before I knew it, every single egg was successfully injected and back into the comfort of their incubator. I peered into the glass door of the incubator, watching my eggs sit there uncracked, and I felt proud of myself. All the fears I had felt just a few minutes ago seemed silly now. I started to feel more confident that I really could do this on my own.

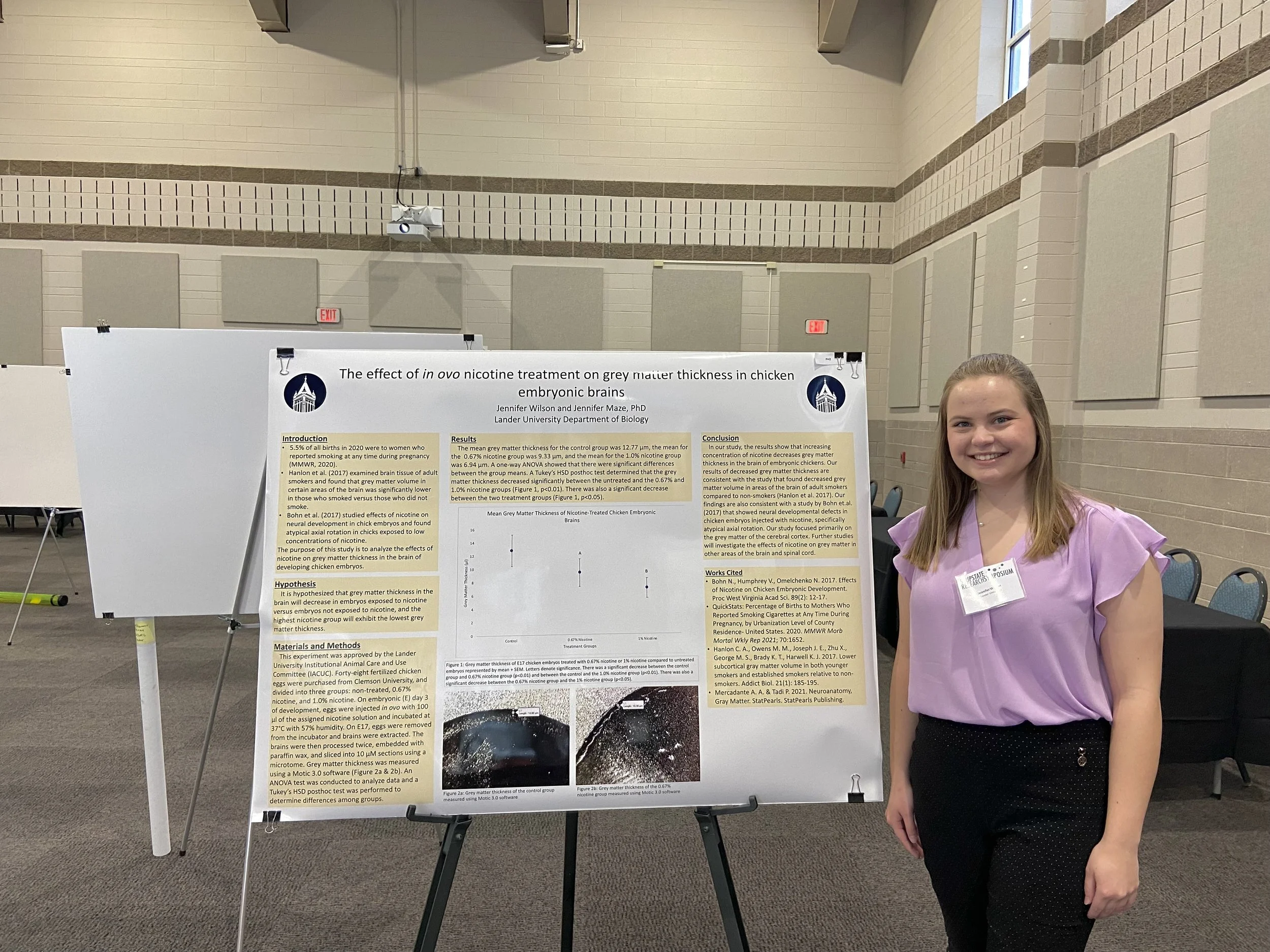

Throughout the next few months of the semester, the confidence I had in myself grew even more as I completed my research. I realized I had more control over how I handled things in the lab, and it stopped a lot of the fears I had about doing research alone. This continued as I learned how to carefully cut through tissue to pop a chicken brain out, embed tissue in wax, and prevent myself from cutting my fingers off with a tissue slicer. At the end of the semester, I presented my research at the SC Upstate Research Symposium and was able to proudly show off my work.

The success of my research was because I did what was best for me in handling my fears. This was by preparing for every single step of my injections as well as preparing for all other parts of my experiment. While it may seem silly to other people, it was what worked for me, and I believe it played a big part in how much I enjoyed my research. Not everyone handles their fears the same way, and I was reminded that throughout this experience.

Jennifer with her poster at the SC Upstate Research Symposium

Jennifer Wilson is from Anderson, SC. She will graduate in May 2022 with a Bachelor of Science in Biology. She conducted undergraduate research within the Department of Biology with Dr. Jennifer Maze. After graduation, she will attend graduate school to continue her love for biology.